Well, we finally made it to Denver’s newest major art museum. Designed as a one-man shrine to the hugely influential and yet largely elusive abstract expressionist, the Clyfford Still Museum opened with much fanfare in December.

|

| Clyfford Still Museum |

Though it feels a bit irreverent to poo-poo any development

in Colorado’s art offerings, we must admit that we have consciously put off

this visit as long as we possibly could in hopes that we might be able to avoid

publicly airing our less than enthusiastic sentiments. Trust us, these thoughts do not come without a

great deal of guilt; and here we must confide that we are looking over our

shoulders and whispering nervously like children hatching an evil scheme as we

write. It’s not that we aren’t excited

to have a large, expensive, and well-hyped new museum in town. And, we certainly don’t HATE the thing-

especially not the way that 36 year-old Carmen Tisch does. In early January, Tisch was arrested at the

museum after causing $10,000 worth of damage to a large iconic painting titled “1957-J-No. 2” by beating it with

her fists and then pulling down her pants and rubbing her behind against the

canvas just before falling on the floor and urinating on herself. Wow- now that’s some hate!

|

| Clyfford Still, 1957-J-No. 2 |

No, no, we certainly don’t hate it. Maybe it’s best to say that the whole thing

just leaves us feeling a bit ambivalent. Still is unarguably one the most important

American artists. He played an instrumental

role as an early pioneer of Abstract Expressionism, the art movement that put

American artwork on the map in the 1950s and that contributed greatly to the

creation of a distinct American artistic identity in the post-WWII period. Still began developing his iconic style early

in the development of the Ab-Ex movement and his large color-field paintings rival

in beauty and importance those of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Hans

Hoffman.

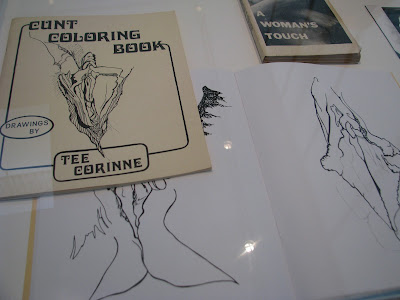

Despite its historical importance and theoretical

contributions to subsequent art movements, Abstract Expressionism has long been

criticized by feminist and post-colonial critics for its elitist and

patriarchal perspectives; and much writing has been dedicated to the machismo

displayed by many of its male practitioners.

In many respects, Still may have lived up to the elitist and pretentious

stereotype of the male Ab-Ex artist. Despite

his influence, Still became critical of the commercial art world soon after his

rise to prominence and remained throughout his life fairly isolated from the

larger Ab-Ex movement. He was extremely

selective in showing and selling his artwork; only allowing about 6% of the

work to ever be sold, and refusing to participate in any public exhibitions

between 1952 and 1959. He also became

increasingly insistent that his artwork should only been seen in highly

specific contexts; and especially insisting that his paintings be seen solely

with other Clyfford Still paintings.

Upon his death in 1980 Still’s estate, which contained

approximately 94% of his life’s production, was closed off to researchers and

the public. His will stipulated that the

estate would be gifted to any city that would build a museum dedicated to the

research and display of solely his artwork.

All of this leaves us in a bit of a conundrum. Should the extraordinary emphasis that Still

placed on the viewing context of his artwork be seen as the manifestation of a self-indulgent

megalomaniac or as a brilliant precursor to contemporary concerns with

immersive environments and site-specificity?

While Still’s work certainly has historical importance, does his work

have enough contemporary relevance to merit the enormous financial investment

that was required to realize this project?

And finally, while the museum holds an enormous collection, how long can

a museum that displays only one man’s artwork really keep the viewer’s

attention? If you are a lover of Clyfford

Still’s work, perhaps indefinitely; otherwise, maybe a visit or two will

do.